Unlocking the Radical Potential of Naujawan Leadership

The foundations of our collective liberation can emerge from the grassroots power being built by Sikh naujawan today.

Prabjot Singh

February 26, 2021 | 13 min. read

Sikh history has always been driven by revolutionary resistance to any form of gulaami (subjugation/domination) and an unending pursuit of sarbat da bhala (welfare of all of Akaal’s creation). While striving to preserve the Khalsa’s inherent sovereignty, Sikhs of the Guru have simultaneously worked towards the collective liberation of all. This commitment has spurred resistance to the imperialist Indian state since its “independence” in 1947—defying both its coercive state apparatus as well as its genocidal nationalist identity.

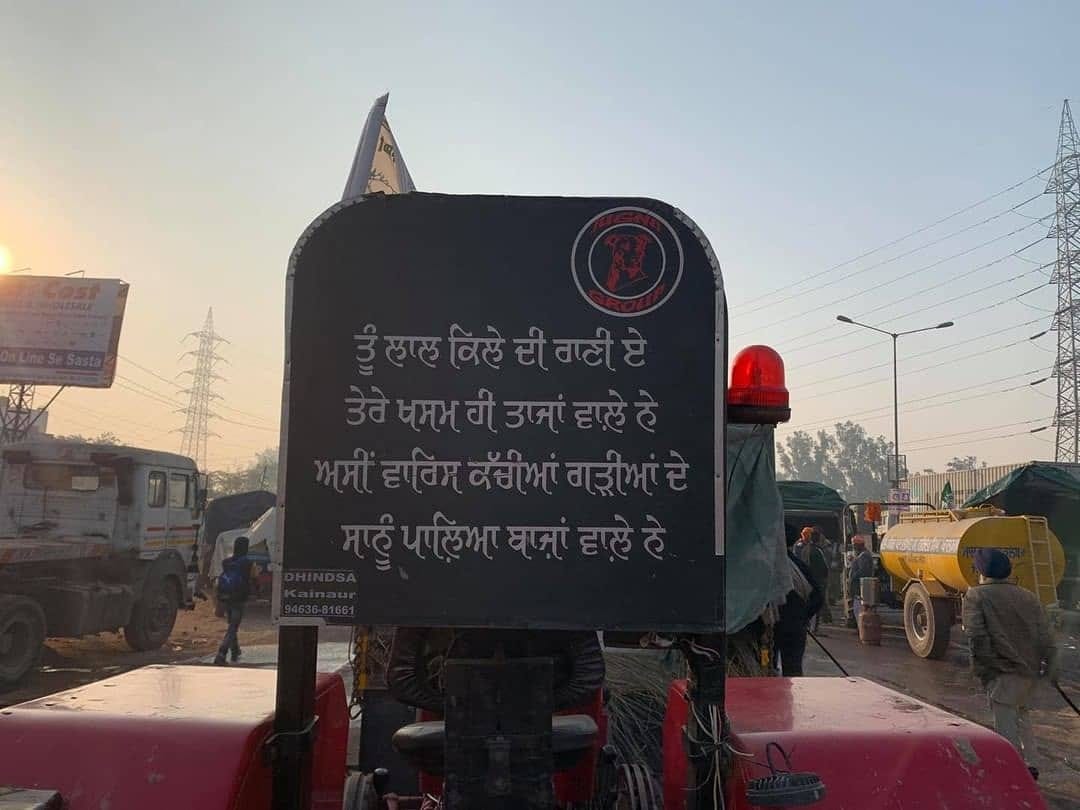

Inspired by this legacy, Sikh naujawan raised the Nishan Sahib at the Lal Qilla (Red Fort) on January 26 as another challenge to Delhi’s imperialist domination of the subcontinent.

In response however, many commentators have aligned themselves with nationalist narratives demonizing the Red Fort action as the result of “extremist” conspiracies to supposedly undermine the farmers’ struggle. This knee-jerk response is largely due to the pervasive violence of Indian nationalism as well as the internal shortcomings of top-down leadership styles within the farmers’ movement.

Rather than focussing on the Indian state’s repressive violence leading to the shaheedi (martyrdom) of Bhai Navreet Singh and the arrests of well over 100 naujawan within Delhi, some union representatives are using conspiracy theories to consolidate their own power by removing committed activists from the Morcha. At the same time, Indian security forces have tightened their cordons around various protest sites and facilitated fascist violence by BJP & RSS goons on January 28 & 29.

Taking stock of the current realities on the ground, the energy of those supporting and participating in the Morcha today needs to constructively address the crisis of leadership and focus on the next stages of the movement.

Much has already been said about the historic blunder of those union representatives who chose to alienate factions within the movement instead of focussing on the common struggle. While a lot of social media chatter continues to fixate on polarizing and overly simplified debates around January 26th, this focus obscures the actual violence of the state and the radical potential the Morcha continues to represent.

To carry this movement forwards, it is imperative that naujawan regroup to:

challenge the violence of Indian nationalism,

resist authoritarian patterns of internal leadership, and

organize grassroots networks of power to uproot Delhi’s domination over the region.

Sikh Struggle or Farmers’ Movement?

Sikh spirit has been a driving force in this Morcha from day one. From the spirit to clash with tyrants sitting on the Delhi takhat (throne), to the principle of sarbat da bhala that creates an inclusive atmosphere for diverse participants, and the anchoring institutions of seva, langar, and vandd ke chhakna that have been the foundations of the Morcha.

Despite this, some have been aggressively pushing a narrative that this is a “farmers’ movement, not a Sikh struggle” in a bid to erase Sikh participation and symbols from the movement. This false dichotomy depends on Indian nationalism’s warped worldview that is threatened by any alternative non-Indian identity. The argument is equivalent to saying that #BlackLivesMatter does not have a place within a movement for prison abolition in the US, even though Black lives are disproportionately affected by the policy and participating in unprecedented numbers.

There is no doubt that the current mobilization is immediately focussed on repealing the three “farmer laws.” Despite this however, it is not made up solely of farmer unions and their cadre. This is a mass movement in revolt against Delhi’s authoritarianism in the subcontinent, neoliberal globalization, and the fascist project of a Hindu rashtra (nation).

Dalits, Adivasis, liberals, leftists, anti-fascists, Sikhs, and countless ethnic groups and spiritual traditions have all been galvanized in this resistance. The immediacy of repealing the farmer laws does not mean that other perspectives must be sidelined and erased—these intersections of oppression and resistance are inseparable from the Morcha. Mutual respect and cooperation are crucial for diverse entities to flourish in the face of the oppressor—rather than recreating the homogenizing approach of the state.

None of these respective movements (including the Panth) is claiming to exclusively represent “the” overall movement or trying to “hijack” it, all of them are mutually enriching the analysis and mobilizing the strength of all those oppressed by the Indian state and imperialism. There are vast ideological and political differences amongst the unions within the Sanyukat Kisan Morcha itself, let alone the diversity within the hundreds of thousands of participants. It is possible for these diverse entities to co-exist within the broader movement without being erased or censored—this minimal degree of mutual respect for diverse identities and political opinions is the backbone of any successful mass movement.

In the current farmers’ movement, caste is relevant, gender is relevant, class is relevant, and Sikh liberation is also relevant. While the farmer unions’ politics are focussed on repealing the three laws, Sikh activists are awakening protestors to the fact that Delhi should not have the power to pass exploitative laws across the subcontinent in the first place. Drawing on the legacy of the Sikh sangarsh (struggle) and advocating for Khalistan in this context does not take away from the strength of the overall movement or divert focus from repealing the laws, just like Dalit activists advocating for mazdoor (labourer) rights and caste abolition does not undermine the overarching movement to maintain kisan ownership over land.

Nationalism and Genocide

In response to the events of January 26th, nationalists of different stripes (including liberals, leftists, and fascists) in different spheres (media outlets, unions, and politicians) swiftly joined forces to condemn Sikh resistance. This response to the raising of the Nishan Sahib is nearly identical to the political landscape leading up to the invasion of Sri Darbar Sahib in the 1980s.

In this leadup, the Sikh panth as a whole was collectively projected as an “enemy within” as Sikhs demanded respect and self-governance. In response, the government intentionally spread mass disinformation to create a pretence for anti-Sikh violence. As a result of Indian nationalism’s militaristic commitment to “defending its borders,” any political expression outside the frame of Indian nationalism and the state is portrayed as a violent threat to its very existence. This can be seen in the criminalization of secessionist advocacy post-1962 and the brutal genocidal violence unleashed in regions like Punjab, Kashmir, and the Northeast. India continues to assert and defend its boundaries boldly—and extrajudicially, by “eradicating those who step outside the line.”

The combination of majoritarian political structures with the intertwining of Hindutva and Indian nationalism is what makes the Indian state an “ethnic democracy” using ‘hegemonic control’ and ‘violent control’ against non-Indian/Hindu communities. When these communities step outside the realm of ‘hegemonic control’ to challenge their assimilation and subordination, the state employs ‘violent control’ to reassert its domination. This has been the case with Sikhs and other resisting communities who are permitted to exist within the state’s administrative structures with some basic civil rights—contingent on their submission to the nationalist project. When these communities step outside of this framework to claim their dignity or exercise autonomous power, they are faced with the genocidal violence of the state apparatus and fascist mobs.

Anyone who steps outside of the boundaries of Indian nationalism is portrayed as a villain that has no legitimacy in public discourse and can justifiably be eliminated (ie. killed). This is the logic that continues to justify Sikh genocide since the 1980s. The enforced “peace” since the decline of the armed Sikh sangarsh is dependent on maintaining the omnipresence of repressive state violence—and making this felt upon the bodies and voices of potential Sikh dissidents today.

The demonization of the Nishan Sahib is intricately intertwined with this dynamic and the fascist violence unleashed in the days following January 26. In a moment of political assertion, Sikh symbols are portrayed as “anti-national” and inherently violent because they represent a rejection of Indian nationalism and a challenge to the Indian nation-state. Instead of acknowledging genuine Sikh sentiments as a ground reality, nationalists demonize resistance to India as a sinister conspiracy—”orchestrated” from Pakistan, the diaspora, or by political parties.

When you look closely, the only tangible difference between the actions at the Lal Qilla on January 26 and the naujawan violently clashing with police on November 26 is that some of the farmers’ leadership immediately felt the boundaries of Indian nationalism being “violated” by Sikhi. This is why nationalist leaders and some union representatives responded so venomously towards the Sikh expression of sovereignty and resistance. Whereas some have genuinely internalized the discourse of “patriotism,” others explicitly sought to distance themselves from the action as an attempt to save themselves from the genocidal impulse of Indian nationalism. Those condemning the Lal Qilla action the loudest are those who succumbed to state pressure, when they should have been celebrating the Sikh spirit within the Morcha and resisting the state’s narrative justifying genocidal violence.

Without successfully challenging the violent structure of Indian nationalism, it is impossible to address the oppressive dynamic of power underlying the three agriculture bills.

Failures of Authoritarian Leadership

There is no doubt that the “official” leadership of the Morcha is failing on several fronts. While there is a disconnect between the union representatives and the masses participating in the Morcha, incompetence and internal rivalry are also damaging the cohesiveness of the struggle. From the beginning of the Morcha, many union representatives have illustrated an authoritarian working style which disregards the sentiments and aspirations of the hundred of thousands actually driving the movement. They have competed with each other to control the stage, ostracized naujawan, and refused to discuss disagreements or suggestions from the sangat on numerous occasions.

The official leadership has repeatedly fallen short of the expectations of the people bearing the weight of the movement. When they gave the call for Dilli Chalo in November, some unions “ordered” everyone to stop wherever the police set up barricades. Sikh naujawan refused to abide by this timid strategy and swept away every obstacle with jaikaray until they reached Delhi. Several union representatives went on a tirade at this time, calling these naujawan traitors and agents of the government for trying to “sabotage” the movement. After January 26, they appear to be repeating a similar strategy.

Despite the strategic victory of entering Delhi and occupying the premier symbol of Indian imperialism, the same representatives accepted defeat and took a completely defensive posture while parroting the media narrative. This is the same media they were dismissing as “Godi media” until the 26th.

Some of the representatives not only condemned the Red Fort action but went to the extent of holding fasts for their “atonement” and physically replacing Nishan Sahibs with the Indian flag during “tiranga sadbhavna” rallies in an attempt to prove their “patriotism.” This defeatist approach by the union leadership is what emboldened the fascist mobs of the BJP & RSS to launch violent attacks at several protest sites with the full support and cooperation of the police.

The habits of some union representatives are replicating the authoritarian tendencies of the state itself—policing protestors, imposing decisions without consulting participants, and seeking to centralize decision-making power in their own hands. In the wake of January 26, several of these representatives have successfully used the same totalitarian strategy of dictatorships around the world—manufacturing an illusory external enemy and using fear-mongering tactics to consolidate their own power base.

To cover up their own shortcomings and unwillingness to consult those participating in the Morcha, several representatives took advantage of the internet shutdown to amplify their own voices while demonizing other factions within the movement itself. Members of the Sanyukat Kisan Morcha declared Lakha Sidhana, Democratic Students Association, Students for Society, Deep Sidhu, and the Kisan Mazdoor Sangarsh Committee as “traitors” of the struggle. They had earlier done the same thing with BKU (Haryana) leader, Gurnam Chaduni, until faced with public pressure to reverse that decision. Some even went to the degree of physically stopping participants from defending the KMSC stage when it was under attack on the 28th.

Unless the union representatives immediately turn away from their appeasement of Indian nationalism and dictatorial style alienating naujawan—they will face increasingly sharp challenges internally or else sabotage their own movement through sheer arrogance and stubbornness.

This authoritarian tendency needs to be replaced with collective leadership from the grassroots. This is the only effective way to mobilize the Morcha’s greatest asset—the vast diversity of thousands who have gathered in militant opposition to Delhi’s imperialism.

Liberating the Subcontinent

The long-term value of genuine naujawan leadership however, is not just in replacing union representatives with social media icons or other personalities. Instead, it is in transforming the model of leadership altogether.

The Khalsa’s prampara (tradition) has always been one of sanjhi agvaaee (collective leadership) and hannai hannai meeri (the rejection of any form of domination—whether that of an external political power or an internal hierarchical structure). As long as any self-appointed leader seeks to break from this prampara by imposing top-down decisions and continuing ego-driven rivalries for control, our struggles and movements will always end in disappointment.

These are the lessons that Sikh naujawan have learnt over the past decade—from movements for the release of Sikh political prisoners, to the Sarbat Khalsa, and Bargadi Morcha. As long as aspiring politicians act as “representatives” or gatekeepers, they will continue to bottle up the kaum’s rage through ineffective bureaucratic structures or manipulate widespread jazba (passion) for their own electoral ambitions. While these individuals hold the levers of the community’s power with no accountability, the collective will always be sacrificed to their narrow self-interest. This has been illustrated by Akali leaders like Harchand Longowal and Prakash Badal.

Genuine leadership is not about giving speeches on stage or herding people like sheep and demanding that they obey your decisions. This is why the role of naujawan has been markedly different this time and why this Morcha got to this point in the first place. After rejecting top-down forms of leadership and taking the reins, naujawan unleashed the potential of the Morcha when power was diffused throughout the sangat. If it were not for the initiative and commitment of these naujawan, the Morcha would still be sitting at the borders of Punjab rather than Delhi.

Despite the games being played by some of the unions, dedicated naujawan must continue to drive this Morcha forward by building the means of collective leadership where power lies in the hands of the sangat. Naujawan have the responsibility to ensure ekta (unity) in this movement while still maintaining their own independent platform and holding all representative factions accountable for shortcomings.

This grassroots power is not just a check on internal powerbrokers and politicians. The Khalsa’s tradition of hannai hannai meeri provides a radical political vision for our future as well. A vision that is based on liberation and grassroots power that is capable of challenging the state’s coercive structures. Combined with the Sikh principles of sarbat da bhala and sanjhivalta (radical inclusivity/co-existence), this praxis offers the building blocks to forge solidarity across the subcontinent through grassroots networks of power to ultimately uproot Delhi’s imperialist domination of the region.

This struggle has mobilized the marginalized and oppressed across the entire subcontinent—going much further than simply repealing the three laws. The foundations of our collective liberation can emerge from the grassroots power being built by Sikh naujawan today.