Saka ate Siyasat: translating Sikh history into political consciousness

The original Punjabi version of this article was published in the June 2005 issue of Sikh Shahadat and has now been translated for readers of the Panth-Punjab Periodical. Despite being nearly twenty years old, the questions and challenges posed by Dr. Sewak Singh remain relevant before Sikh naujawan and those claiming the mantle of Sikh leadership today. While June ‘84 sparked a legendary struggle that has left its mark on Sikh history, those seeking or proclaiming to represent and lead the community must engage in serious introspection to understand why the objectives and aspirations of the Sikh sangarsh for Khalistan have not yet been clearly formulated and internalized by large swathes of the sangat. While posing these questions, the article also provides clarity on the foundational steps required to translate the dard (pain/anguish) of June’ 84 into political consciousness/commitment as well as a revolutionary mode of politics–altogether different from the status quo of the different factions of the Akali Dal.

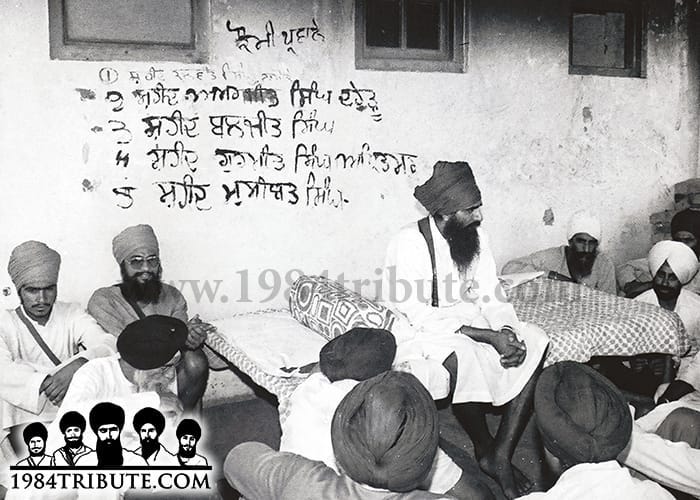

“The day the Indian army invades Sri Darbar Sahib, that day the foundation stone of Khalistan will be laid.”

These words of Shaheed Sant Jarnail Singh Bhindrawale hold deep significance that must be fully understood in order to grasp their implications for generations of Sikhs to come.

Other than a handful of commentators who are either ignorant or simply dishonest, there is widespread consensus that the Indian army’s invasion of Sri Darbar Sahib was an attack on Sikhi itself. At that time, Sant Jarnail Singh Bhindranwale was entrusted with the role of the sentinel/watchman of the Sikh qaum (collective) which is why so many misunderstand–or intentionally misconstrue–the invasion as an attack on Sant jee or because of Sant jee. Because Sant jee so clearly manifested the traditions of the Khalsa, he has been transformed into a historic Sikh figure despite being our contemporary. As we reflect on this legacy, the question before us today is how the panthic politics of the past three decades have understood–and implemented–the karni and kathni (the deeds and words) of this historic figure. While we saw 12 years of active struggle, we are also now looking back on decades of so-called “peace”.

The roots of contemporary Sikh political consciousness are based in the Singh Sabha lehar (movement) which provided the base for many Sikh organizations today outside of traditional schools of thought. This lehar had the maturity to diligently move forward, but the absence of clear politics gradually had a negative impact on the qaum. During the lead up to Partition in 1947, the desire for Sikh raj (governance/sovereignty) was a distant dream for only a handful of Sikhs; those who considered themselves “educated” behaved as though they were completely illiterate when it came to building a popular movement around this critical issue.

Even after 1947, demands for a “Punjabi Suba” (a semi-autonomous state within India based on linguistic identity) were made as Punjabis [rather than as Sikhs] based on the advice and guidance of this same intellectual elite. Although the people were mobilized on the basis of their panthic jazba (passion/commitments), these sentiments were not adequately translated into concrete political objectives. Similarly, dreams of an autonomous region were never going to be realized either because India is not a federal entity. Instead, any achievements within this political structure would end up being the equivalent of a starving person being content with eating rotting food that gradually destroys whatever little bodily strength remains (ie. despite its obvious harms). Punjabi-speaking areas were also placed in the cradle of the Hindi belt by granting them to Himachal, Haryana and Rajasthan. As a result, we gained a ‘Punjab Suba’ without its own capital, high court, or control of its own water or electricity.

Frustrated by the economic, cultural, and political consequences of these developments, the Akalis were being pushed toward demanding a separate state at each turn. This is most clearly demonstrated by the Centre government’s actions–repeatedly breaking off negotiations with the Akalis and adopting a strategy of torturing and killing Sikh naujawan (youth) in staged ‘police encounters’. The state of Sikh politics was so deplorable during this period however, that even despite the gravity of June ‘84, the Akalis accepted a settlement along the lines of the Rajiv-Longowal Accord simply out of a desire to gain limited political power. The nature of this agreement was the equivalent of the police handing over the body of a Sikh naujawan–murdered in custody–on the condition that the body be cremated quietly without protest or uproar. Despite gaining a majority Akali government in 1985, Sant jee’s proclamation regarding the “foundation stone” was completely absent from their politics.

Up to this point, most of whatever written material or audio/video has been produced related to June ‘84 or the sangarsh has been based on government sources which proclaim Sant Bhindranwale to be a creation of the Congress; that the Akalis were polarizing figures who flip flopped on their stance; and that Sikh naujawan were manipulated at the hands of Pakistani agencies. Even Sikh and other non-state writers have been dependent on government sources for their information which leaves us with an incomplete understanding of the period altogether. Beyond that, those sympathetic to Sikh perspectives have consistently pushed sensationalist narratives which conjure horrifying spectacles of state violence that emphasize feelings of fear and dread. This approach has been like dumping buckets of paint on an empty canvas rather than painting a nuanced portrait with a fine brush to ensure precision and control over the result. According to this perspective, because Indira Gandhi had pre-planned the Darbar Sahib invasion, all of the ensuing events were the result of a conspiracy related to electoral politics. In reality, the impact and pervasiveness of this skewed narrative reduces the significance–and actually trivializes–the saka (major historical event) and the subsequent Sikh sangarsh.

When we reflect on our history, it is clear how the Khalsa panth has always responded in the face of adversity and persecution. Following the shahadat (martyrdom) of Pancham Patshah (Guru Arjan Dev jee), Chheve Patshah (Guru Hargobind Sahib jee) asked the sangat to contribute their best naujawan, horses and weapons–this is how they prepared for the conflict that lay ahead. Following the shahadat of Nauve Patshah (Guru Tegh Bahadur Sahib jee), Dashmesh Pita (Guru Gobind Singh jee) not only raised an army but made the Khalsa Panth shastardhari (armed) and bound to rehit (discipline). Following the Chhota Ghallughara, Sikh jathe (units) adopted a gurmatta that they would not allow Punjab to become a part of the Afghan empire; they would become the sovereigns of Punjab themselves. Following the Vadda Ghallughara, Sikhs not only defeated Abdali–they obtained fateh (victory) and conquered Delhi; Sikh raj was ultimately established in Punjab. After every devastating saka, victory would kiss the Khalsa’s footsteps.

Following saka Nankana Sahib and Guru ka Bagh, the Akalis became the centre of attention throughout the subcontinent and around the world. They made the English taste the steel of their discipline and organization. At this opportune moment, ‘Mahatma' Gandhi called the Chabiyan da Morcha the first victory in the “battle of independence”. The heirs of Chanakya and Shankaracharya shrewdly co-opted the Akali victories to serve their own interests rather than actually further the Sikh cause. As the saying goes, “the child had died but the protective cord remained intact” (ਮੁੰਡਾ ਮਰ ਗਿਆ ਤੜਾਗੀ ਨਾ ਟੁੱਟੀ) [ie. the Akali Dal remained intact, although the purpose of it's existence–furthering Sikh political interests–was eventually sacrificed at the altar of Indian nationalism). From that day until the battle at Kargil [and even until today], Sikhs have fought for the “freedom of the country”. Who knows much longer they will continue to fight this fight, but it is clear that justice or liberation are never exchanged for this wage labour. In this regard, the words of Sirdar Kapoor Singh are particularly relevant:

“Every victory belongs to whomever is represented by the flag under which the war is fought and won. The victory is of that flag itself and the objectives which that flag represents, not of the individual bravery of those fighting. Sikhs should have enough political sense to understand that until they achieve victories under the Khalsa’s own flag–according to their own declared [military/political] objectives–even if they conquered the whole world, this would not be a victory for Sikhs or the Panth, nor would such a victory be useful to furthering Sikh aspirations.”

When Sant Bhindrawale spoke about ‘laying the foundation for Khalistan’ if Darbar Sahib was invaded, this also meant that for the first time since 1849, Sikhs would wage war for their own declared political aspirations. The ensuing conflict between the Delhi Takhat and Sri Akaal Takhat was solely about political sovereignty. India does not have any issue with Sikhs being a distinct ‘religious minority’ as long as questions of sovereignty are not raised.

After June ‘84, the tone of Sikh politics revolved around resisting the “Brahminical state”–which had previously been referred to as the “Central government” until that point. The difference afterwards was that the Badal Dal focussed on opposing the Congress while other factions declared the RSS their enemy and sometimes mentioned “Khalistan”–sometimes explicitly, sometimes implicitly. Every policy or action taken against Sikhs was viewed with the lens of conspiracy; rather than proactively building our own foundations/institutions, this constant refrain/complaint about “anti-Sikh” policies kept the wheels of Sikh politics turning. This dang tapaaoo (disingenuous) approach to politics consistently raised June ‘84, November ‘84, and the endless blood spilled in the subsequent sangarsh–but only for the limited purpose of gaining votes or establishing themselves and their legitimacy as Sikh “leadership”. In reality, this tendency has been even more dangerous and harmful than the direct attacks of the Indian state. Direct attacks by the Indian state remind us of our identity and heritage which turn us back toward our weapons (ie. our independent strength) while electoral politics in the name of panthic dard (pain/commitment) has gravely desecrated the jazbat (passions/emotions) of the people. The psychological impact of this is that Sikhs have largely become cynical/hopeless which is a shameful testament to the conduct of Sikh academics, dharmik leaders, and politicians. This process has been further entrenched due to a lack of clarity about our political objective, and the absence of firm commitment to proactive strategies/policies that actually address our concrete issues [ie. our political discourse largely remains limited to sloganeering].

The attempts of some of our own people to demand an apology from Congress leadership or the Indian parliament as a form of reconciliation, or “achieve” justice for 25,000 corpses through monetary compensation, is in reality performative self-serving politics. Financial compensation is given by governments to the victims of accidents, not to rebels. Despite these obvious shortcomings, we cannot deny the genuine emotions/intentions of some advocating for such efforts. They are conscious of their independent dharmic existence/identity, but they hesitate to speak about [ie. are ignorant of] their independent political existence/identity. According to this logic, it is perfectly acceptable to become a shaheed for a dharmic issue, but raising the relevance of politics/sovereignty in this context is seen as jarring and uncomfortable.

This distorted political understanding has a residual negative impact on dharmic principles as well. This is why the narrative that Sant jee desecrated Sri Akaal Takhat by taking weapons into the precint gained widespread acceptance. Sri Akal Takhat is the manifestation of power/strength. It was revealed by the Guru that wore the two swords of Miri-Piri, and fought a war over the emperor’s hawk–declaring that the emperor’s throne would be next. Dashmesh Pita issued the hukam (command) of appearing in the Guru’s darbar (court) adorned with weapons. The concept of dharam in the minds of people who do not understand this bears resemblance to the Buddhists who sat in meditation in the face of the armies of Mahmud Ghazni.

The demand for a separate state was unequivocally established through the armed struggle but the framework and viability of Khalistan was not clearly articulated in those circumstances. Based on the statements of Sikh politicians however, it seems like Punjab would simply be renamed “Khalistan” and those wielding the government’s power structures would simply be replaced. In reality, this simplified (and problematic) approach would not be building upon the foundation of Khalistan laid by Sant jee, nor would it truly represent the form and structure of Khalistan. Sant jee’s comments about the foundation of Khalistan are clear that this would be the foundation but it would only be the start of a long journey. It was clear that the attack was inevitable; Sant jee’s comments were simply an indication that we would only understand on that day when the enemy’s hand went straight to our pagg (dignity) and a line would then be drawn in blood.

Being conscious and committed to maintaining your independent political status is a necessary prerequisite to establishing an independent state. Sant Bhindrawale consistently reinforced the idea that “Sikhs are a separate qaum, this is an undeniable reality” many times but manifesting this tangibly requires ideological commitment/clarity and firm commitment. The mass popular uprising immediately following saka ‘84 illustrated a firm commitment but the difficult process of ideological transformation and achieving ideological clarity was not immediately apparent for large portions of the population. This is why the building [of ideological clarity/commitment] is to be erected brick by brick–not all at once.

Even when the sangarsh began, the overground/political leadership did not go through a qualitative shift. During these difficult times, individuals were simply replaced rather than undergoing a transformation of leadership altogether. There was already limited political consciousness [clearly formulated], but the imposition of unqualified and inexperienced individuals among the frontlines of the leadership began to reverse even the limited progress that had been made up until that point.

What we needed at the time was grassroots work to ensure ideological clarity and commitment to the vision and objective of Khalistan. Popular support could then be mobilized politically/overground based on these foundations but this task could not be completed at the height of the sangarsh itself. The basis of the overwhelming support was Sikh sentiments and commitments which drove countless soorme (warriors) towards shaheedi, but the political arena of struggle to establish raj was fought without clear political consciousness or formulation of this objective.

While this issue could not be implemented during the sangarsh for a number of obvious reasons, it still has not developed in the following decade of so-called “peace” either. This stagnation itself raises grave questions about the [credibility and legitimacy of] individuals claiming positions of Sikh leadership. Fomenting political opposition, critiquing so-called panthic leaders, or merely issuing statements and announcing protests in response to anti-Sikh incidents or policies however, is like breaking the mud off a buffalo’s back to decrease its weight. Lacking clear ideological vision and an intimate relation with the struggle is an egregious crime for anyone claiming to lead a qaum fighting for its liberation. This is also a crime for every Sikh that thinks they have the answers, especially those that are capable of writing or speaking a few words (ie. consider themselves highly educated).

A contemplative understanding of Gurbani and Sikh history is then crucial to this task of theorizing the Sikh struggle and developing our political theory. Without this we cannot build clear ideological frameworks, successful political movements/tactics, or free ourselves from gulaami (slavery/subjugation).

Those who cannot articulate/disseminate the concept of Sikh raj–grounded in Gurbani, history and the contemporary sangarsh–in the conditions of the 21st century; such leaders–even after three decades–have not understood the essence of the words of that Sant Jarnail Singh Bhindranwale who became shaheed before Sri Akaal Takhat, when he said “the day the Indian army invades Sri Darbar Sahib, that day the foundation stone of Khalistan will be laid”. Without reflecting on and remedying these issues, such self-proclaimed leaders will be lost in the pages of time–amongst those “leaders” that came out with their arms raised during saka June ‘84.

Dr Sewak Singh | @SikhShahadat

Dr. Sewak Singh is a prominent Sikh thinker and activist who completed a PhD in Linguistics at Punjabi University, Patiala. During his time as a student, he was central to reviving the Sikh Students Federation immediately after the Indian state’s brutal counterinsurgency. He is a former Assistant Professor of Religious Studies, and also served as the Assistant Dean of the College of Arts & Sciences at Akal University. He is a leading Sikh academic who has done extensive work on Gurbani grammar, Punjabi linguistics, and the cultural politics of Punjab in the context of colonialism and nationalism.